Clinging to God and grammar

In times past, progressive politicians described those they despised as clinging to “God and guns.” I suspect that we are not too far from a time when they will insult those they deplore for clinging to God and grammar. That might sound an odd claim, but the days are coming rapidly to an end when it was morally acceptable to think that language, among its many functions, had a positive relation to reality. Today, dictionaries and grammars look set to become relics of a bygone age of evil oppression.

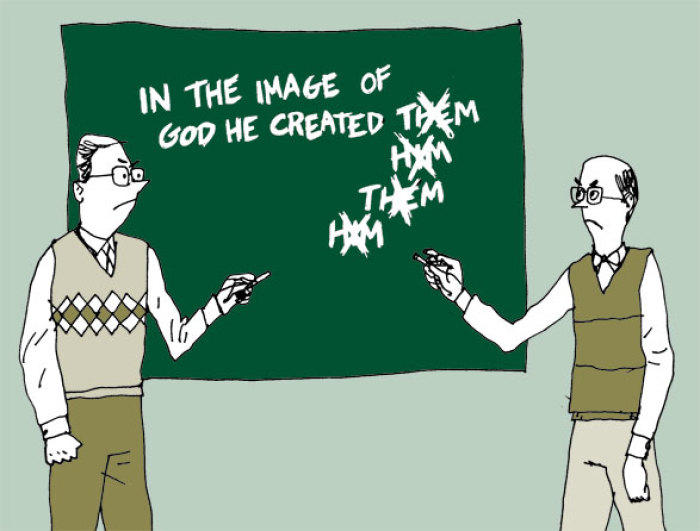

Take, for example, the trend of specifying preferred pronouns on everything from Twitter to business cards — a fascinating sign of our times. Even some Christians are participating. Whether people do it out of genuine confusion, positive commitment to queer theory, or in pre-emptive anticipation of it becoming the equivalent of Havel’s greengrocer shop sign in our brave new world, it is an action that most would have regarded as absurd even five years ago. Most (probably) still regard it as absurd today. But that old consensus is crumbling, just like every other once-unquestionable Western cultural belief. Queerness is moving rapidly from arcane, implausible theory to practical, everyday reality.

While many on the right default to accusations of cultural Marxism when confronted with such iconoclasm, I would argue that this latest trend is reminiscent of nothing so much as Friedrich Nietzsche’s haunting statement in Twilight of the Idols: “I fear we are not getting rid of God because we still believe in grammar.” This sounds odd but in the context of his argument, it makes sense. What Nietzsche is saying here is that language tricks us into thinking that it expresses reality but it does not do so; rather, it constructs concepts that it presents as real and seductively traps us into thinking of the world in particular ways.

If ever there was a philosophical position that placed the individual and his (or her or zir) will at the center of the universe, then this is it. Such radical nominalism may be nonsense but, like sex, it sells, appealing as it does to our intuitive sense of freedom and desire for autonomy. And rather like current attitudes toward sex, it recreates the world’s purpose making us feel good about ourselves. To accomplish this, it asserts that God – and all that He created, from male and female to notions of right and wrong – are simply linguistic constructs, mere con tricks that capture the imagination of the unthinking herd.

Nietzsche was prescient. The current battles for the future shape of Western society are being waged most fiercely in the area of language. That would not be so worrying if the fight was about conforming language to reality. For example, to object to a demeaning racial epithet would seem not merely philosophically legitimate but morally imperative, a way of preventing the constructed category of race from being used to demonize another human being.

Human nature is real; we all share it, and that places moral responsibilities upon us. But when we decry pronouns that assume the reality of bodily sex, we are coming close to denying the universal truth that all humans are embodied beings. Indeed, we are tearing away the very foundation upon which common humanity and a common humanitarian ethic can be built.

Josef Pieper expressed an insight similar to Nietzsche’s, though he does so with foreboding and dread rather than joy, and with far more political prescience. In an important essay, “The Abuse of Language and the Abuse of Power,” he observed:

Once the word, as it is employed by the communications media, has, as a matter of principle, been rendered neutral to the norm of truth, it is, by its very nature, a ready-made tool just waiting to be picked up by “the powers that be” and “employed” for violent or despotic ends.

Pieper is saying that once language is detached from any greater reality, it becomes a weapon in the hands of the powerful for the manipulation and the abuse of others. When we consider this in light of Nietzsche’s observation on God and grammar, a rather grim truth becomes evident: The abolition of grammar merely changes one authority for another. The old God might be held to his (pardon the phrase) word, as reflected in reality. The new gods are but raw power writ large, unattached to anything beyond themselves.

Ironically, that means that the thing Nietzsche feared above all — the herd mentality and its mindless morality — is precisely what will emerge, because the individual has nothing with which to resist the power of the strong. That is what we are witnessing in the unthinking rush to specify pronouns among people who have never considered their bodies to be unreliable guides to their gender.

The battle over pronouns on social media and in public spaces, as trivial as it seems, is actually of great importance. The abandonment of reality that queer ideology demands may be marketed as nothing more than sensitivity toward the feelings of others, but in fact, it is imposing a view of the relationship between language and reality that makes the latter nothing more than a function of the former. And the reason it is being pressed with such force is that it is a bid for power by those who deem any and all categories oppressive except those they invent themselves.

They hate reality. And they hate the God who made that reality and the grammar and syntax by which it is expressed. Nietzsche knew it; it is a shame that some Christians seem rather confused on the matter.

And as for politicians who despise those who believe in a God-given reality: You can take my grammar and dictionary from me when you tear them from my cold, dead hands.

Originally published in First Things.

Carl R. Trueman is a professor of biblical and religious studies at Grove City College. He is an esteemed church historian and previously served as the William E. Simon Fellow in Religion and Public Life at Princeton University. Trueman has authored or edited more than a dozen books, including The Rise and Triumpth of the Modern Self, The Creedal Imperative, Luther on the Christian Life, and Histories and Fallacies.