For Church to be relevant, it must avoid childish things

In Milan Kundera’s 1975 novel The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, Czechoslovakian president Gustav Husak — the “President of Forgetting” — declares, “Children! You are the future!” Kundera goes on to say that this is true “not because they will one day be adults but because humanity is becoming more and more a child, because childhood is the image of the future.”

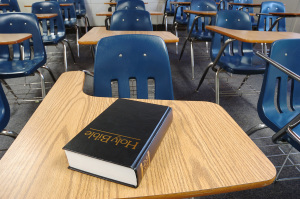

Douglas Murray’s recent Spectator article on the Church of England confirms the Czech writer’s prophetic insight. Canterbury Cathedral’s “silent disco” in February and Peterborough Cathedral’s upcoming November “rave” certainly speak of a childish age. These buildings were built for the serious and sacred purpose of worship; that was why generations invested many decades and resources in their construction. To use them now for events that could easily be held in a makeshift tent says much about the sacred nature of the trivial hedonism of our age.

It also says much about a church that has long since lost any confidence in the Gospel codified in her 39 Articles, Book of Common Prayer, and Book of Homilies. Recent reports reveal that she is increasingly abandoning the word “church” in favor of other descriptions, such as “community.” And anyone gazing on The Queen’s Window in Westminster Abbey is more likely to recall scenes from SpongeBob than be awed by thoughts of the transcendent creator and redeemer of mankind.

Lose the Gospel, return to childishness; this seems to be the order of the day.

Indeed, this childishness is the inevitable outcome of the kind of theological liberalism that has dominated so many churches for several generations. Ironically, theological liberalism has often been the product of some of the finest minds. Friedrich Schleiermacher, the notional father of Protestant liberalism, was one of the dazzling intellects of his day. The Tübingen School, which did huge damage to orthodox belief, boasted an array of stellar scholars. And in the Anglophone world, figures such as C. H. Dodd and John A. T. Robinson were men of true academic substance. Yet liberal theology, as it has shaped the worshiping life and liturgy of the Church and the attitudes of her people over many years, seems only to have tended toward one practical direction: childishness.

Paul thought that the outsider who blundered into a Christian service in his day would be overcome with a sense of the holiness of the God being worshiped. Today’s hapless intruder into Peterborough Cathedral might be overcome, too — by the deafening noise and cringeworthy sight of grown-ups cavorting like teenagers as the two great spiritual pathologies of our modern world, desecration and childishness, come together.

This fusion of the profane and the puerile makes sense: The more that human beings supplant God as the measure of all things, the smaller they become. They cannot grow up, for, lacking a given end, there is nothing really for them to grow into. And as the holy is desecrated by human power, so human beings are themselves reduced, no longer bearers of the divine image but mere lumps of matter attached to wills.

Athanasius in the fourth century could declare that God became human so that humans might become gods. Human beings were exalted by the act of the transcendent God. Today we might say that humans have made themselves gods so that God might be reduced to mere man. More than that, that He might become a childish construct whose concerns never move beyond the immediate needs of the human condition, whether these be entertainment, politics, or simply feeling good about ourselves. Of course, liberals do not have a monopoly on this: Any professing Christian who speaks of “the big man upstairs” or who apes the childish idioms and brickbats of our current political moment is guilty of the same.

Ours is a childish age. Kundera was prophetic on that score. That is not to say that the matters at stake in both church and world are not deeply serious. But the idioms for addressing them have become infantile, and the Church must resist the temptation to follow the world in this. To seek relevance therefore requires not capitulation to, or emulation of, the infantile, but rather a recapturing of what it means to be an adult. The Church must bear witness to a grown-up faith. That means that we need a renewed sense of the holy, the sacred, and the transcendent. And that must start at the top, where it is too often most absent.

The X feeds of many of the loudest Christian pastors today indicate little difference from the categories, attitudes, and preoccupations of secular leaders. This is a sad dereliction of duty; of all people, pastors should point heavenward, to where Christ sits and intercedes for His people. That is their calling, as prosaic and limiting as some clearly seem to find it. If Christian leaders are childish, what hope is there for their congregations? For the Church to become relevant, it must eschew childish things and recapture her priorities. She is first and foremost the place where Christians worship a holy God who, at great cost, delivered us from “our childish ways” (1 Cor. 13:11).

Originally published at First Things.

Carl R. Trueman is a professor of biblical and religious studies at Grove City College. He is an esteemed church historian and previously served as the William E. Simon Fellow in Religion and Public Life at Princeton University. Trueman has authored or edited more than a dozen books, including The Rise and Triumpth of the Modern Self, The Creedal Imperative, Luther on the Christian Life, and Histories and Fallacies.