‘Friends’: Were they really there for us?

We’re heading into a big weekend of entertainment. Cruella’s hitting theaters and Disney+. A Quiet Place II will be making noise as well. But for many, the weekend’s entertainment crown jewel will be on HBO Max: The Friends reunion special.

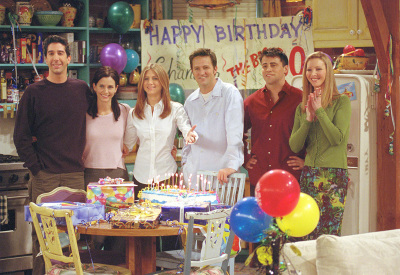

Twenty-seven years ago, Friends premiered on NBC and introduced us to six young Manhattanites who rarely worked but could always afford coffee. I, along with much of America, can name the characters from memory. I know about Joey and Chandler’s comfy recliners, Phoebe’s smelly cat, Monica’s Thanksgivings, Rachel’s famous ‘do. And this is from a guy who’s watched just a handful of episodes. Imagine how much actual fans of the show know.

Friends’ last episode aired May 4, 2004, drawing a staggering 51.1 million viewers. Yet the show’s cultural influence has barely waned since then. In fact, fans’ love might’ve only grown—with new generations introduced to the overly sexed sextet thanks to the ageless wonder of streaming.

Clearly, America loves the show, and it has for a long time. But it’s also an illustration of something else: power.

Toward the end of the Friends reunion trailer, James Cordon (one of a legion of special guests who’ll show up during the reunion special) says something interesting: “What you have given so many people is an experience of huge comfort,” he said. “We felt like we had these friends.”

It’s true.

After a hard day of work or school, people could retreat to the sanctity of the girls’ apartment or Central Perk and unwind, just like the characters themselves did. They could laugh. They could commiserate. They could find a sense of belonging that maybe we all struggle to find outside our television screens. It didn’t matter if we were 13-year-olds with acne or 66-year-olds with bad knees; we could feel like we knew these beautiful, quirky, hopelessly cool people. Sometimes we knew more about them than we knew about our workmates or next-door-neighbors or, honestly, even our sons and daughters, our mothers and fathers. They were our friends. And as such, for some, they became a template of what we thought real friendship should look like.

For many fans—particularly those suffering through a difficult season—shows like Friends become a little oasis in a stormy life. When a marriage is on the rocks, when the kids won’t listen, when your boss is getting ready to fire you, you can slip into a comfortable sitcom and, for 30 minutes, life feels OK again. And maybe, those 30 minutes give you the boost you need to push on.

Sure, Plugged In (the entertainment outlet for which I work) could pick apart the sexual practices we saw on Friends, and justifiably so. But even many longtime Plugged In users—maybe some of you reading this very post—would give the show a pass. The relationships superseded the problems. And I totally get that.

That’s what sitcoms do at their best: They form relationships. They always have. That’s why we still see The Dick Van Dyke Show and I Love Lucy in reruns, more than 60 years after they first aired. Yes, they’re funny, but that doesn’t completely explain why these and other shows still pull people to them. It’s all about relationship. And relationships are powerful.

We are social creatures. God designed us that way. We’re built to love one another. “Though a man might prevail against one who is alone,” we read in Ecclesiastes 4:12, “two will withstand him—a threefold cord is not quickly broken.”

But the Bible also says (in 1 Corinthians 15:33) that “bad company ruins good morals,” and that can be even true when we talk about the company we keep with sitcom characters.

Now, just because we watch Joey and Chandler discuss their sexual exploits, that doesn’t mean we’re automatically going to sleep around. It’s not as simple as that. But when we open our hearts to a TV show, we inherently allow that show to impact not just how we feel in the moment, but how we think after the show is over. Those relationships we see onscreen—and the relationships we form with those onscreen characters—can subtly shape how we engage with the world around us, just like our real-world friends do.

We talk often about the power of media and entertainment. It’s a big reason why Plugged In exists. But the biggest power that entertainment holds sprouts from the very best of roots: relationship. It’s not so much the act of seeing a movie or show that impacts us; it’s that we care so deeply about what we see. We care about the characters, even though they’re just amalgamations of actors on screen and words on a page.

The Friends theme song promised viewers, “I’ll be there for you.” The love we’ve seen for the show proves that it made good on its promise for many folks. But we should always remember that the show, and its memorable characters, didn’t come alone. They brought—and still bring—problems, too. And the more we love our favorite characters, the more aware we should be of how they may be impacting us.

Paul Asay is a senior editor at Plugged In, Focus on the Family's media discernment website. He's the author of several books (including the recently published Beauty in the Browns) and lives in Colorado Springs with his wife, deaf dog and several unruly houseplants.