Is America really going atheist? Rise of the ‘nones’ masks growth of healthy churches

Scientific American reported in 2017 that “since 1990, the fraction of Americans with no religious affiliation has nearly tripled, from about 8 percent to 22 percent.” The magazine predicted that “by 2020, there will be more of these ‘nones’ than Catholics, and by 2035, they will outnumber Protestants.”

Well, maybe or maybe not. There is a lot going on to counter the conclusion that atheism soon will be America’s dominant “faith.”

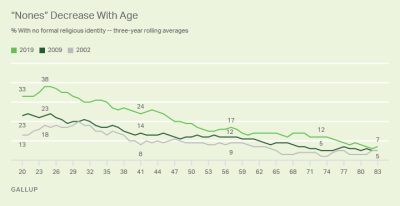

A 2020 Pew Forum survey supports the rise of the “nones.” Twenty-six percent of Americans identify with no denomination. That’s higher than the Catholic Church, the single largest denomination. But it’s still dwarfed by the more than 65 percent claiming a Christian affiliation, albeit a drop of 12 percentage points from 10 years ago.

Currently, 43 percent of adults identify with Protestantism (down from 51 percent in 2009); 20 percent with Catholicism (down from 23% in 2009).

The Real Story

“Mainstream” Protestant denominations have been losing adherents for decades and failing to attract new ones. The same goes for Catholics, whose church has been rocked by a long-term sex abuse scandal. The slowness of their decline may be partly due to the arrival of millions of immigrants from Mexico and Central America, who tend to be Catholic.

In any case, people who used to reflexively cite the faith of their childhoods are now being more honest in surveys.

“The nones are simply those who until recently would have identified with a Christian denomination just because that’s what their family has always been,” Glenn Stanton of Focus on the Family summarizes in a Federalist article. “But their pastors know they are just CEO Christians (Christmas and Easter Only). Beyond that, it’s crickets attendance-wise.”

In “The Triumph of Faith: Why the World Is More Religious Than Ever,” Rodney Stark of Baylor University, writes, “The entire change [toward none-ness] has taken place with the non-attending group.” He added, “In other words, this change marks a decrease only in nominal affiliation, not an increase in irreligion.”

Competition among religious organizations “strengthens faith by weeding out the lax and unappealing denominations and energizing the others to maximize their outreach,” he writes.

A Pew study in 2015 cited in the Washington Post found mainline denominations were losing about one million people annually. At the same time, the percentage of “nones” rose in almost inverse proportion to the losses in mainline numbers.

Why the Exodus?

Some researchers cite the replacement of orthodox Christian theology in mainline churches with modern, liberal viewpoints, and the opposite occurring in surging evangelical congregations.

A 2016 Canadian study showed that “the theological conservatism of both attendees and clergy emerged as important factors in predicting church growth.”

“It’s not the whole story, but here’s an argument for at least part of what has happened,” wrote Ed Stetzer in the Washington Post. “Over the past few decades, some mainline Protestants have abandoned central doctrines that were deemed ‘offensive’ to the surrounding culture: Jesus literally died for our sins and rose from the dead, the view of the authority of the Bible, the need for personal conversion and more.”

Mr. Stetzer, executive director of the Billy Graham Center at Wheaton College, explained that “if the mainline Protestant expression isn’t different enough from mainstream culture, people turn to other answers.”

For instance, in one 2016 study, only 56 percent of clergy and 67 percent of worshipers from declining churches agreed with this statement: “Jesus rose from the dead with a real flesh-and-blood body leaving behind an empty tomb.”

By contrast, 93 percent of clergy members and 83 percent of worshipers from churches with numerical growth affirm a literal resurrection.

The headlines on church decline are usually unbuffered by the kind of insights provided by Stanton, Stark and Stetzer.

“Americans are growing more secular all the time — which is one reason why Trump voters are so angry,” Salon.com reported in March 2017.

“In U.S., Decline of Christianity Continues at Rapid Pace,” said the Pew Research Center on Oct. 17, 2019.

“As Christianity’s Popularity Declines, More Americans Identify As Religiously Unaffiliated, Study Finds,” Newsweek reported, citing the Pew study.

Only occasionally does the media read the tea leaves as Stetzer does, as in The Washington Post’s “Liberal churches are dying. But conservative churches are thriving,” by David Haskell, professor of religion and culture at Wilfrid Laurier University in Ontario.

“Conservative Protestant theology, with its more literal view of the Bible, is a significant predictor of church growth while liberal theology leads to decline,” he wrote, basing it on his study in the Review on Religious Research.

What to Make of it All?

Church statistics can be illuminating or misleading, depending on interpretation.

Two conclusions emerge: The media seems to be cheerleading the notion that American religious belief is fading. And the media may be missing the big story — liberal churches are declining while Bible-believing churches are growing.

In the Book of Revelation, Jesus warned the church at Sardis that “you are dead.” He told the church at Laodicea, “Because you are lukewarm, and neither hot nor cold, I will spit you out of My mouth.”

Being lukewarm may placate secular critics, but it may not lead to growth.

Faced with life’s challenges, the “nones” eventually are going to seek answers to life’s questions.

So far, the evidence suggests that liberal theology may not satisfy them.

Robert Knight is a writer for Timothy Partners, Ltd. He is a regular weekly columnist for The Washington Times, Townhall.com, OneNewsNow and others. His latest book is “Liberty on the Brink: How the Left Plans to Steal Your Vote.”