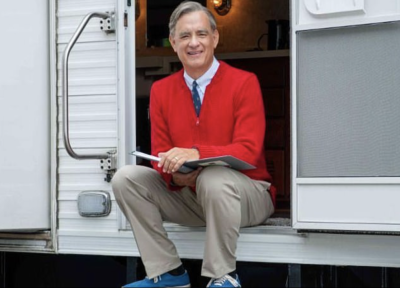

Mr. Rogers and his good book

Mr. Rogers, the television host played by Oscar nominee Tom Hanks, wanted children to be his neighbors. Commonly unappreciated are the deep Biblical dimensions of this seemingly simple hope.

In its 1991 Final Report, the bipartisan National Commission on Children found that “many children are in jeopardy. They grow up in families that are in turmoil…. Some of these children are unloved and untended.”

Implicit to these comments (which I know because I helped write the report) was concern that these problems were getting worse. Recent social and legal changes — eased access to divorce, a surge in non-marital births, and consequent fatherlessness — may have contributed to adult freedoms and choices. However, the effects on children were mostly negative, adding to their sense of being unloved and other fears.

Fred Rogers understood this. He might have entered into the “culture wars” over marriage and family. Yet, as his biographer Maxwell King notes on a related point, he “worried that such public posturing would cause confusion with the parents and children” who watched his show. Mr. Rogers held that “kindness, understanding, and openness in relationships” would have more effect. Like a battlefield medic, he was there to nurture the wounded young and to help them begin to heal.

Some conservative critics of his show, “Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood,” would take its creator to task for telling children to feel good about themselves, even if behaving poorly; what they really needed was a good dose of personal responsibility. Such judgments missed the larger cultural picture of adult behaviors less ready to put the needs of children first.

For Mr. Rogers, his work was actually the Bible in action. Even regular watchers of “Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood” were (and are) sometimes surprised to learn that he was an ordained Presbyterian minister. Indeed, in the 895 episodes of the show that he wrote, directed, and acted in, he seldom openly discussed matters of religious faith.

All the same, the very premise of “Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood” was profoundly scriptural. It rested on one of the most vital of Biblical passages, where Jesus lays out the Second Great Commandment: “Love your Neighbor as Yourself.” For Fred Rogers, children were his most important neighbors, in the rich Gospel sense of that word, and the focus of his pastoral care. They were beings made in the image of God. There is merit in author Amy Hollingsworth’s depiction of Mr. Rogers as a latter day Saint Francis of Assisi, who once said: “Preach the gospel at all times; if necessary, use words.”

Like St. Francis, Mr. Rogers did live a simple life, avoiding alcohol, tobacco, meat, evening parties, and even most television. Every day, he rose at about 5 A.M. to pray for those in need and to read passages from the Bible chosen to prepare him for the special tasks of that day. For himself, he asked “for the goodness of heart to be the best person he could be” toward each child or adult that he would meet.

In other ways, Fred Rogers was complex. He is properly remembered as a quietly effective advocate for racial reconciliation, for engaging severely handicapped children in his broadcasts, and for other acts of inclusion: all of which he understood as following in the footsteps of Jesus. His 1969 testimony before a U.S. Senate subcommittee in favor of federal funding for the nascent Public Broadcasting System is legendary and still used today to shame politicians, such as Mitt Romney, who have had the temerity to seek cuts in PBS support. Fred Rogers was also, it appears, a lifelong Republican.

Did he know success? Certainly, his show aired on about 400 PBS stations and, given its format and intended audience, enjoyed fairly solid Nielsen ratings.

Statistics, though, fail here. Anecdotes are better. The new film, It’s a Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, wonderfully recreates an episode witnessed in 1998 by Esquire magazine writer Tom Junod. Mr. Rogers and he were caught in a Manhattan rainstorm. As usual, the taxis disappeared. The two took a subway. It was late afternoon and the train car was crammed with school children, heading home. “Though of all races,” Junod reports, the children “were mostly black and Latino, and they didn’t even approach Mr. Rogers and ask him for his autograph. They just sang,” joining spontaneously in his show’s opening tune, “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” and turning “the clattering train into a single, soft runaway choir.”

Fred Rogers died in early 2003, age 74. At the funeral, his friend the Reverend William Barker shared Mr. Rogers’ favorite Bible passages. He was particularly fond of the Psalms, and had memorized Psalm 121. It concludes:

The Lord will keep you from all evil; He will keep your life.

The Lord will keep your going out and coming in from this time forth and for evermore.

Television cannot confer immortality. However, reruns and YouTube do provide a digital shadow of life after death. “Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood” continues to reach children, especially those under stress, with a simple, reassuring message: “You are special. You are loved!"

Allan Carlson, an historian, received an appointment in 1988 to The National Commission on Children from President Ronald Reagan. He is an affiliated scholar of the Faith and Liberty Discovery Center on Independence Mall in Philadelphia, Pa.