Southern Baptists and institutional sin

In 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King launched a historic crusade for the end of racial discrimination and segregation in Birmingham, Alabama. Focal points for demonstrations were downtown streets, and especially an inner-city area around Sixteenth Street Baptist Church (an African-American congregation later to be bombed, killing four Sunday School children).

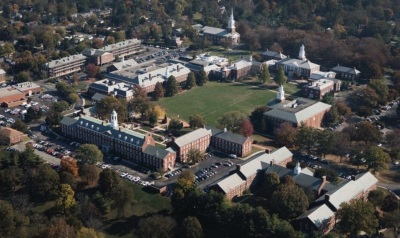

Howard College—now Samford University, a Baptist school—was nestled in a valley miles south of the downtown area. People there were almost oblivious to the historic actions underway across the hills and valleys from their institution.

Two student leaders in Howard’s Ministerial Association were troubled that they understood so little about Dr. King and the movement he was launching.

They decided to seek him out.

The pair found Dr. King at the A.G. Gaston Motel, one of only a couple of hostelries then open to African-Americans near downtown. Dr. King assigned one of his aides to meet with them.

When the students got back to Howard College, word had already reached there about their visit with Dr. King. One of the students was stunned when a theology professor quipped, “I could ruin you with every Southern Baptist Church in Alabama.”

The professor seemed to be warning the student about what could happen to his career if he supported Dr. King and his civil rights movement.

To its credit, the Alabama Baptist Convention years later would take many steps toward reconciliation, and now numbers African-American churches and institutions within its denominational fold, as well as multi-racial congregations. Samford University—the former Howard College—has a broadly diverse student body.

However, in 1963, the young ministerial student was starkly awakened to what would be understood years later as institutional sin.

Dr. Al Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, and himself a graduate of Samford, recently released a report bringing to light a history of racism and support for slavery by the founders and other leaders of the Louisville Seminary, the “flagship” educational institution of America’s largest non-Catholic denomination.

“This report documents the contradictions and complexities of the experience of Southern Baptists and race in America,” says the paper.

Some critics would argue that the report is unnecessary in light of admirable efforts to overcome the sins of the past. Yet confession and repentance for institutional sin is a vital step toward corporate health.

Above all, it is the means for releasing the grace of God upon an organization. No individual and no group of individuals can escape judgment apart from God’s cleansing. Institutional sin is not an abstraction, but a hard reality that distorts social values and deforms the society it influences.

Institutional sin is shared sin, that of a community, or corporate body. The Prophet Isaiah sees God in His transcendent holiness, and declares: “Woe is me for I am ruined! Because I am a man of unclean lips, and I live among a people of unclean lips...” (Isaiah 6:5)

Isaiah himself may have been a man of pristine personal character, but he knew he shared in the sins of his community because he had not confronted the corporate evil around him.

Institutional sin is compounded sin. “The belief in white supremacy that undergirded slavery also undergirded new forms of racial oppression,” says the Seminary’s report. “The seminary’s leaders (in its early days) long shared that belief and therefore failed to combat effectively the injustices stemming from it.”

The institutional religious establishment that Jesus confronted was made up of leaders to whom the Lord said, “... woe to you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites, because you shut off the kingdom of heaven from people; for you do not enter in yourselves, nor do you allow those who are entering to go in.” (Matthew 23:13)

Thus, institutional compounding of sin happens when the organization traps people into its twisted worldview, demanding that they hold to the same poor values and bad practices enshrined in the institution.

This means that institutional sin is credentialed sin. Evil is given the stamp of approval by the organization’s supposed good name. The professor who challenged the ministerial student in 1963 was not himself a racist, and had no intention of carrying out his threat. Yet the scholar’s jesting words were intimidating to the student’s ears. The teacher had weighty credentials: he held a doctorate from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary.

Institutional sin is ratified sin. The organizational community embraces its worldview as normative. For example, most white people in the segregation era never even thought of speaking against it. The institutions that educated their leaders, formed their interpretations of history, and blessed the segregated lifestyle were largely silent. The assumption was that racial separation and the discrimination that it led to was the way society worked.

It was passively accepted by the mass, influenced by their institutions, until Dr. King took to the streets of Birmingham and other cities.

It would be dangerous for those who were not part of such a society to be smug, judgmental and dismissive. There is now also a proliferation of institutional sin. For example, there would be no #metoo movement if people long ago who knew about the sexual abuse in Hollywood’s entertainment institutions had brought the evil to light rather than trying to conceal it.

There are many other institutions in all fields of human endeavor that are sharing, compounding, credentialing, and ratifying evil. Society cannot be healthy and culture wholesome as long as sin lurks in the nation’s institutional camps.

Confession is not only good for the human soul but for the corporate soul as well.