The problem with (mis)remembering the Holocaust

Today, on the 75th anniversary of the liberation of the infamous Nazi death camp known as Auschwitz, the world marks International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

The millions who each year visit Auschwitz, as well as the Holocaust museums in Jerusalem, Washington D.C., and elsewhere become witnesses to an era of almost unimaginable cruelty.

They, and we, are told to “never forget.” And we shouldn’t. But, it is crucial not only that we remember, but how we remember.

Last week, in the online magazine TLS, Nikolaus Wachsmann reflected on the plea of camp victim Zalman Gradowski that future generations would “form an image” of the “hell” of Auschwitz.

“But,” Wachsmann writes, “the Auschwitz of popular imagination often bears little relation to the Auschwitz Gradowski had lived and died in. As a global emblem of evil, the camp has become unmoored from its actuality.”

For example, Wachsmann relates that “It is often said ... that Auschwitz was a different planet, so alien that even birds did not sing there.” But that’s not true. The camp’s surroundings were “rich in wildlife.” So rich, in fact, “that employees of IG Farben, the German firm that enslaved thousands of prisoners, went birding together, while a trained ornithologist among the SS guards meticulously surveyed the local species… for scholarly publications.”

In other words, there is a very real human tendency to mis-remember the grave evils of history: to imagine that they happened in a different world; to think that those who perpetuated such evil, or those who scandalously remained silent and complicit, were somehow different kinds of people than we are.

Exacerbating this tendency is the modern illusion of moral evolution. That somehow we are more enlightened and tolerant than they, having moved on from the bigotry of our human past.

That moral chronological snobbery is not only wrong, it’s dangerous, creating a blind spot to the evils and horrors of which we are capable.

In his 1993 Templeton Prize address, Chuck Colson described the realization that came to Holocaust survivor Yehiel Dinur at the trial of Adolf Eichmann:

“Dinur entered the courtroom and stared at the man ... who had presided over the slaughter of millions. The court was hushed as a victim confronted a butcher. Then suddenly Dinur began to sob and collapsed to the floor. Not out of anger or bitterness. As he explained later in an interview, what struck him at that instant was a terrifying realization. ‘I was afraid about myself,’ Dinur said. ‘I saw that I am capable to do this ... Exactly like he.’”

Jewish philosopher Hannah Arendt wrote about the Eichmann Trial in her book Eichmann in Jerusalem. She found Eichmann neither “perverted nor sadistic,” but “terrifyingly normal.” She called this the “banality of evil.”

Hidden evil flourishes. Throughout history, evil has often hidden in plain sight, enabled by its terrifying normalness and the moral blind spots we self-inflict. And it continues today … Consider how the world is mostly silent as China sends Muslim Uighurs to concentration camps.

Or, why the voices of so many victims of sexual abuse in Hollywood, in corporate America, in homes, and churches are only now, decades later, being heard? Just last Friday, hundreds of thousands of people marched, for the 47th time, to draw attention to the government-subsidized slaughter of millions of pre-born babies.

Hans Scholl, who, along with his sister Sophie, was executed in 1943 for founding an anti-Nazi student group called the White Rose, once described his struggle to understand evil. Marveling at the beauty of the German landscape he wrote in a line reminiscent of the Psalmist, “Does God take us for fools, that he should light up the world for us with such consummate beauty . . . And nothing, on the other hand, but rapine and murder?”

Then Scholl asked a question we should all ask: How ought we respond to evil? “Should one go off and build a little house with flowers outside the windows … and extol and thank God and turn one’s back on the world and its filth? Isn’t seclusion a form of treachery of desertion? I’m weak and puny, but I want to do what is right.”

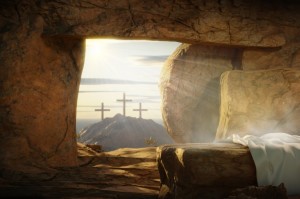

In Christ, God entered the world in order to confront, and ultimately defeat, evil. He calls us to confront evil as well, but let’s be clear: The world Christ entered was this world. The evil He confronts is the evil we too are capable of. As we remember, let’s be sure to remember that.

This article was originally published at BreakPoint.