What Makes Church Tick? Here's The How and Why

When seeking to understand what makes a church tick, I've learned to ask two questions: What is the gospel for this church? When is the Kingdom for this church? I usually then suggest that the answers to these two questions together (the what and the when) shape how a church lives. The 'what' (soteriology) and 'when' (eschatology) questions shape the way we answer a third question, the 'how' (ecclesiology) question (this is the stuff we study HERE at Northern Seminary)

I find this analysis helpful in examining Rod Dreher's most recent book The Benedict Option. Surely, Dreher is proposing an answer to that third question: how do we live as Christians in the world as the church? For him the world is a culture grown hostile to Christianity. He is giving us an ecclesiology for how to live in it.

I suggest we can understand Dreher's vision for church better by asking, What is the gospel for Dreher? What is his eschatology? How is his understanding of the church as revealed in The Benedict Option formed by these two questions?

Dreher's Gospel

For many reading Dreher, there is no good news in The Benedict Option. Christians have lost the culture war in North America. The ways Christians in America have tried to change the culture has backfired. Indeed, even the church has been compromised. Christians are in a heap of trouble in the West.

To some therefore, it might appear that Dreher's Benedict Option has no gospel. But this is an overstatement. I think Dreher's good news to Christians goes something like this: If we are faithful, we can survive this mess!

In the first chapter of The Benedict Option, Dreher gives an impressive summary of the intellectual history that brought us to this point in North America. It relies on many of the authors I read in graduate school way back when including Hauerwas, Milbank, David Bentley Hart, Charles Taylor, Zygmunt Bauman, Phillip Rieff, Christian Smith and of course Alasdair MacIntyre (FYI I read many many other authors in grad school than these white men. These are just the authors Dreher draws from). Dreher nicely popularizes these thinkers to show us the historical factors that led us to this point in American culture.

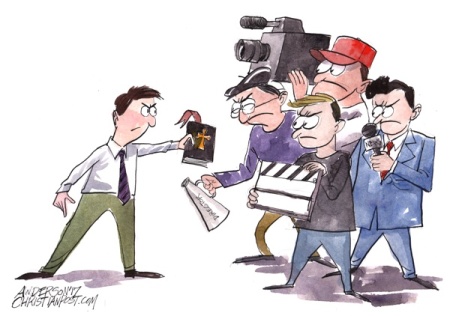

This all leads to Dreher's conclusion. Set up by these various historical factors, it's now too late for Christians to try to fix the culture through the means so many Christians have been trying. We're being overwhelmed. It's time for Christians to withdraw. For Dreher this is the big news (if not the good news).

According to Dreher, it's now too late for Christians to try to fix the culture.CLICK TO TWEET

Dreher then goes on to argue that if we will withdraw, become faithful and get our act together, we can survive and flourish, calling the rest of the culture to see the way of Christ at work in our lives. It's worth noting that Dreher is not telling us to withdraw for withdrawal's sake. NO, the goal here is step back, survive, flourish as Christian communities, and then impact the culture with our witness. If there's a gospel in The Benedict Option, this is it.

But is that a true gospel? Gospel is, by its nature, an announcement of something unforeseen, something God has done to overcome the world, something we didn't expect or know before hearing the good news of what God has done in Christ to inaugurate a new world. Dreher's message seems to be about preserving something old.

Dreher's gospel doesn't seem like a proclamation of God doing something dynamic and world-changing through Jesus Christ. Rather it's Dreher calling on the church to withdraw from the culture to rebuild an older, in his view Classic, insulated culture, or as he puts it, "the restoration of Christian belief and culture" (p.50).

That means that Dreher already has an ideal version of culture in his views. His discussion about that seems unusually focused on sexuality and the nuclear family. And, while I agree that we should examine the American church's self-expressivist and romanticist views of marriage, it's as if Dreher is locked into some 1950's version of gender roles and nuclear family. (Why does he use gender-excluding pronouns throughout the book?).

The worry for me here is that Dreher's perception of the gospel says: "We have it figured out, this is what it looks like, come join us." It's a posture of preservation from a Christendom that seeks to preserve what it once had in the heyday of its power. It's like golden age logic, and to me, that's no gospel at all.

Dreher's Eschatology

Dreher's book also has a second problem: It's devoid of an eschatology. One might take a look at Dreher's negative assessment of culture and think Dreher is practicing (what used to be called) dispensationalism (James K. A. Smith makes some observations along these lines in this recent article).

Traditionally, dispensationalists have said that Jesus postponed the kingdom to the future. The world is heading to an Armageddon destruction, and we live in 'the church age' where we seek to save as many people from the coming doom of God's judgement, after which the kingdom will come.

Dreher's association of The Benedict Option with Noah's Ark and the Great Flood sounds strangely like dispensationalist end times teaching where the church becomes, according to Dwight L. Moody, a life boat and the world a wrecked vessel, and we are called to save as many as we can.

But even dispensationalism would say that God is in control and taking the world somewhere. Dreher doesn't seem to have that? His book seems devoid of an eschatology. As a result, for Dreher, the task of the church seems to be to preserve for preserving sake. There seems to be no sense that Christians should cooperate and participate in what God is doing in the world in and through His people.

Dreher's book also has a second problem: It's devoid of an eschatology.CLICK TO TWEET

This eschatological void cannot help but shape a church to be defensive. It focuses the church on maintaining in the face of threats. It undermines the very witness we had hoped to accomplish in the first place with this strategy.

Looking to St. Patrick

And so with no gospel and a devoid eschatology we are left with a church incapable of mission. It all leads me to propose another option. Yes, I know. In response to Dreher's Benedict Option, people have already proposed the Augustinian Option, the Zacchaeus Option, the Bonhoeffer Option—Heck, we've even had the Fitch Option! But for the times we're facing I prefer the option offered by St. Patrick of Ireland.

Whereas Benedict withdrew from a declining (yet established) Roman Christianity in Italy, St Patrick moved into Ireland, where there were no signs left of Roman Christianity. As opposed to retreating from a church losing its power, Patrick went humbly, giving up power, to be a missionary to pagans who had previously enslaved him.

For the times we're facing I prefer the option of St. Patrick.CLICK TO TWEET

From Patrick's communities, missionaries were sent (like Columba to Iona, Aidan to Lindisfarne, Ninian, Cuthbert) all over Europe. Again and again, these Irish missionaries took groups of twelve disciples to form communities of presence to all the dark places of Europe. They became present to people in the world. They believed the gospel, that God had made Jesus the Lord of the world, that He still works in the world by the Spirit.

Whereas Benedict became known for preserving Latin Scriptures (and other texts), these Celtic communities were known for translating their prayerbooks from Latin into the vernacular of the people. They famously illustrated these prayer books with the art and images of their various contexts. The presence of God infused their daily lives in the world. And through the Irish, some have said, all of Europe was saved. (The most popular of these works include Thomas Cahill, and George Hunter).

So I applaud The Benedict Option for teaching us the value of community and faithfulness, but, for this time, I suggest that the Benedict Option is in need of a Patrick Option. No doubt the role of the Irish in Christian history has been overplayed, but nonetheless, the example of St. Patrick shows what faithfulness and mission look like together in the forming of communities in Christ. For these times we need more than withdrawal, we need the faithful presence of the Irish.

David Fitch is B. R. Lindner Chair of Evangelical Theology at Northern Seminary Chicago, IL. You can find more of his writing at http://www.missioalliance.org/.