Why the West's indifference to religious persecution

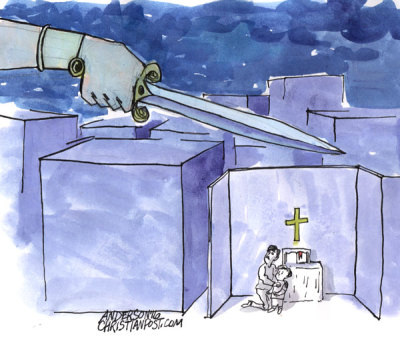

Why do Western nations seem indifferent to the often brutal and blood-soaked religious persecution happening now throughout the world?

This was the concern of Aid to the Church in Need, a Catholic charity, as reported in the Christian Post November 25, by Stoyan Zaimov. It seems the West largely has turned a “blind eye” to the tribulation affecting believers in God.

John Lennon “imagined” a world where there was no religion. In many places, his vision is becoming reality.

The apathy—especially on the part of the United States—is surprising and disappointing, given the traditional commitment to freedom of belief and expression enshrined in the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment. In the original view the primary divide was between evangelicals and Catholics, Christianity and Enlightenment rationalism, a free church and a state church.

However, over time the broader application stretched to the multitude of religions and philosophies. It meant freedom for Christians, but also for the building of mosques, temples, the organizing of atheists, believers in the spaghetti monster, and the formation of an artificial intelligence church, to name a few,

Chaotic and messy, but wonderfully free.

Now, however, there has been an ominous turn that may be causing the United States and Western European nations to turn that “blind eye” to the suffering abroad. Some blame it on “ultra-nationalism,” but that answer is too simplistic.

The deeper reason for the apathy is that contemporary consensus establishments do not have the defense of religious faith as a priority. Some within them may actually be taking grim satisfaction in the attempts to wipe out religions they deplore.

Richard Dawkins has told us that religious faith “can be very very dangerous,” and that “deliberately to implant it into the vulnerable mind of an innocent child is a grievous wrong.” Christopher Hitchens widely opined that “faith causes people to be more mean, more selfish, and perhaps above all, more stupid.”

Both Dawkins and Hitchens might have considered themselves non-establishment types, but many other socio-cultural elites who form our national values consensus agree. In previous Christian Post articles, I have listed those elites: The Entertainment Establishment, Information Establishment, Academic Establishment, Political Establishment, and Corporate Establishment.

The Entertainment Establishment promotes delusion that the sanctioned consensus and its values are true; the Information Establishment increasingly builds a wall of censorship around the consensus; the Academic Establishment revises history, and seeks to lend authenticity by credentialing the consensus and its “experts”; the Political Establishment passes laws and regulations, giving official sanction to the consensus and its now mandated behaviors; the Corporate Establishment, assuming the shift of many in their preferences, quickly steps in to reach new markets shaped by new trends in thought and expression.

So how do these establishments generally view religion—especially the Christianity that gave them their freedoms of expression?

A sampling:

Kevin Sorbo told Fox News reporter Sasha Savitsky that in Hollywood there is “a negativity … towards people who believe in God.” The Hollywood establishment is not open to people with differing beliefs, Sorbo said. The Information Establishment encompasses Silicon Valley and all it symbolizes, along with Big Media. For example, Joy Behar, of ABC’s “The View” opined that Vice President Mike Pence’s “talking to Jesus” in prayer might be a “mental illness.” The Academic Establishment (which does not include the many fine private institutions across the land) credentializes versions of history that present religious belief as the source of many evils. When Professor Timothy Larsen submitted a proposal to a Yale University committee considering important contributors to the “Western Tradition” to include T.S. Eliot, a noted twentieth Christian philosopher and poet, members of the committee suggested mentioning Eliot might be like including “the ideology of the Taliban.” (As reported in insidehighered.com) In the political establishment, many Democrats, at their 2012 National Convention, booed the inclusion of God in their party platform. Currently, Donald Trump meets and prays with pastors, then tweets sometimes ungodly messages. Corporations too quickly watch for cultural trends in the hopes of boosting their corporate image and reaching new markets. Target is the poster boy of this thinking. When some states sought to protect the traditional gender designations on restrooms, Target quickly countered by making its restrooms transgender. One shopper told The Wall Street Journal that “Target picked a side and pretty much said to the rest of us that we don’t matter.”

These examples do not represent all in the establishments. There are dynamic Bible studies in Hollywood reaching celebrities, cells of believers within Silicon Valley, deeply committed academics in major universities and public education, prayer groups and Bible studies in Washington, and many in the corporate business world who see that realm as their mission field, as well as doing business according to principles revealed in the Bible and other religious writings.

Yet the masters and mistresses of the establishments give little notice to such people. They are, in fact, surprised to find believers right under their noses.

If the establishments that set the cultural consensus and its values for millions of people have attitudes regarding religion—and Christianity especially—that range from apathy to outright hatred, how can we expect the nation to prioritize protection of belief and expression for the persecuted abroad, and not turn a “blind eye”?