Artificial Intelligence, Transhumanism and the Church: How Should Christians Respond?

As artificial intelligence and emerging technology continue to develop at breakneck speed, Christians have no choice but to engage given the staggering implications it's already having for ministry and the broader culture, scholars say.

For many followers of Jesus, the explosive use of digital devices like smartphones and an ever-growing number of social media utilities are challenging enough to deal with, especially when it comes to raising children. As leaders in the tech industry place their own children in schools where technology is not available and even home use is discouraged, many are also increasingly concerned about a burgeoning, smartphone-fueled mental health crisis.

But wholly rejecting or ignoring technology will only worsen conditions for everyone, according to two tech experts who spoke with The Christian Post. What Christians need to reject is their ignorance of the subject, they say, and a re-examination of their priorities is in order.

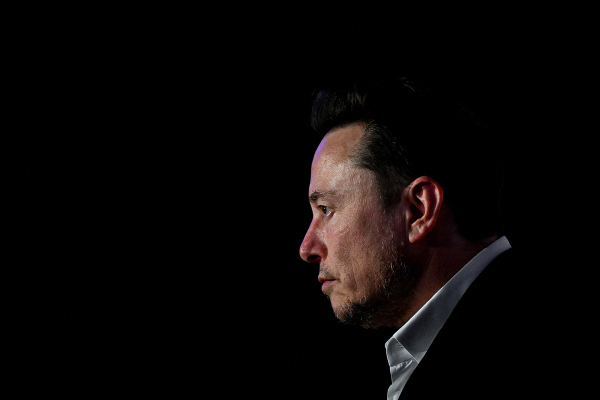

Fabrice Jotterand, a professor of Swiss nationality who teaches at a Wisconsin medical school and is a renowned scholar in neuroethics, recounted in a CP interview last week that most believers are simply unaware that AI technology is in fact already here.

"People think it is science fiction, it's something of the future, or it's in the movies. And I think that there is a kind of naiveté about these technologies," Jotterand said, as this industry is in dire need of voices providing serious ethical and theological reflection. He is presently writing a book titled, The Unfit Brain and the Limits of Moral Bioenhancement.

"We shouldn't say all technology, all AI, is necessarily, inherently bad," he said, arguing that it's vital to distinguish between transhumanism and AI because all too often people mistakenly conflate them.

"Transhumanism is the idea that you're going to transcend human biological nature using technology; at the basis you still have a human being using technology to enhance his or her capacities," he explained.

By contrast, "AI is basically a new entity, an entity that in some ways replicates some of the attributes of the human being."

Yet most of the confusion exists around the notion of embodiment, he went on to say, a confusion rooted in a Gnostic mindset that pervades the transhumanist creed. And it is not an exaggeration to consider transhumanism a religious cult of sorts, one that proposes immortality on its own terms and amounts to the very erasure of what makes us human, he stressed.

Indeed, already these beliefs have taken shape in a futuristic movement called Terasem, which was formed in 2002 by Martine Rothblatt, a transwoman and multimillionaire CEO of United Therapeutics, along with his wife, Bina. Rothblatt also has a robot clone of his wife called Bina 48 who looks like the real Bina Rothblatt and has received many uploads of information from her life. According to its website, Terasem is based on four pillars: (1) Life is purposeful. (2) Death is optional. (3) God is technological. And (4) Love is essential.

The Terasem "Beliefs" page plainly states: "Nobody dies so long as enough information about them is preserved. They are simply in a state of 'cybernetic biostasis.' Future mindware technology will enable them to be revived, if desired, to healthy and independent living."

The movement claims with regard to God being technological: "We are making God as we are implementing technology that is ever more all-knowing, ever-present, all-powerful and beneficent. Geoethical nanotechnology will ultimately connect all consciousness and control the cosmos."

Meanwhile, futurist Ray Kurzweil, who works on Google's machine learning project, has said in recent months that by year 2029 what is known as "singularity" — the total merging of human and computer intelligence — will be achieved.

Jotterand explained that an essential aspect of transhumanism is "that the body is totally irrelevant to our identity as a human being" and that "the body becomes something you can manipulate at will and doesn't have any normative stand in defining who we are as human beings."

In other words, from the transhumanist perspective, what defines a human person is what is inside the brain and if the contents can be uploaded onto a hard drive then that would still be you.

With AI, a larger challenge emerges, namely: "What kind of relationship will humans have with it?" he said. Already headlines are telling of people wanting to marry and have sexual relations with robots.

Other quandaries now upon us, which most Christians never thought they would even have to ask or think about, center on the social status of robots in the law.

"If we define legal personhood based on certain functions or tasks it will mean that the robot has rights, and disabled people or individuals with a handicap of some kind might then have a lesser status," Jotterand pointed out.

"And this is where we need to be very careful," he added. "Are we using these robots and AI to fulfill human ends or are we allowing them to be autonomous and fulfill their own purpose?"

European thinkers have been exploring many of these themes for some time, the professor noted, referencing German philosopher Martin Heidegger's 1926 essay "The Question Concerning Technology," in which he maintains that technology indelibly "enframes" human beings.

Whatever one makes of Heidegger's writings and other work, "think about an iPhone or a smartphone, you [practically] cannot function in this world" without one now, Jotterand said. He urged Christians to consider how much Facebook and Google govern so much of their thinking and daily decision-making.

"My advice would be to be aware that this technology exists and know how it works, but use it to promote the human good and put boundaries [around it]."

"Unless we become the Amish of the world with regard to technology and say, 'Nope, we're not really going to touch technology' ... but then we don't function. And so what we need to do is earn our place around the table and shape these discussions in a way that honors God and protects human dignity."

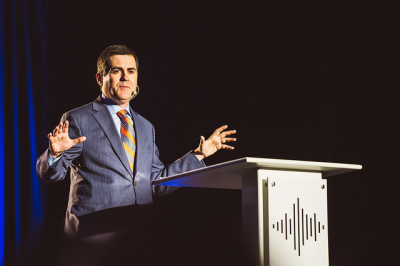

Christopher Benek, who has written extensively on transhumanism for CP and is an internationally recognized expert on emerging technology and theology, said in a recent interview that the first thing for Christians to remember is that almost all of us are already using AI in our cell phones and other digital devices.

"When I start to talk with people [about this subject] I say, 'Let's back up a bit,'" Benek said.

"If we look at God and we have some concept that God created us, that means we are already God's alternative intelligence, as I like to say, God's AI."

Benek is a Presbyterian pastor in southern Florida and the founding chair of the Christian Transhumanist Association. He stressed in the interview that the healthiest way of interacting with this subject theologically is to take what we know about theology and begin to converse about what is helpful, recognizing that AI can be used for evil or good much in the same way nuclear physics can be utilized to either make murderous weaponry or to provide a clean energy source.

"Christ started a redemptive process that we are called to participate in, to actually help in the redemption — Christ has already secured the victory — but as co-creators, like as with a parent and a child, to co-create alongside God. So there is no reason to think that God wouldn't empower us to create AI and create very powerful AI to help in those redemptive purposes," Benek said.

This requires the recognition that all matter is essentially technology, something that is to be stewarded like anything else, he said.

In November, Benek traveled to Japan and was the first ever pastor to speak at the International Conference for Social Robotics.

"What was fascinating was how amazed they were at the insights I had with regard to the robots they were building. And part of the reason I have that insight is that I deal with people who build robots and AI."

The creative processes involved in the making of this technology is inextricably linked to who human beings are and the reflections and iterations of themselves that are projected onto what they build, he explained; and if Christians are formed as people in ways that emulate Jesus Christ, then their technological creations will benefit humanity and further His purposes in the world.

Echoing Jotterand, Benek strongly believes that the Church has no option but to engage these issues immediately and be a part of the ethical conversations surrounding widespread technology use. He recently counseled a foreign government that had solicited his advice (he could not say which country) to invest a billion of their currency toward AI safety.

An additional concern many Christian leaders have today is how emerging technology might thwart our very humanity particularly as it changes the economy and labor market. Southern Baptist leader Russell Moore, president of the Ethics & Religious Liberty Commission, wrote in December that he was especially nervous about driverless cars dependent on AI technology.

"What happens to a view of work when increased automation seems to be constantly 'disrupting' careers and even entire industries? Unlike previous generations of Western people, ours increasingly has little understanding of the world our parents and grandparents lived in, in which one expected to learn a skill, find a job, and remain in it, or perhaps be promoted upward through it, for life. Those days are gone," he said.

"Instead, increasingly, younger people find they must compete in a 'gig economy' where they may change jobs multiple times in a five-year period, if they can even find work at all."

CP asked Benek how churches might respond and minister to those who face potential job losses and the ever-growing crisis of smartphone technology addiction among youth, a problem likely to increase if current trends continue.

"How do we expect our children not to be addicted to a phone if they haven't been formed in the teachings of Christ to know otherwise? If they don't know what an idol is, they are not going to know. We as Christian adults, we have to moderate ourselves on these things," he replied.

"The church has forsaken the gospel to maintain the institution of the church. And so if we continue to worry about property and buildings and not about people then you will continue to see [bad] results and we'll have no one to blame but ourselves."

But Benek believes automation is the biggest opportunity the church has had in front of it since the Reformation to be relevant. He is currently drafting an overture to the General Assembly for the Presbyterian Church of America asking them to consider emerging technology and have some kind of formal council that issues recommendations to churches about how to deal with these issues.

For those who do not think the subject matter is relevant in the church, Benek asks: "Stand up in your pulpit on Sunday morning and look out and imagine half of those people being unemployed. What are you going to do when that happens?"

"Tech will reform the church if we do not get involved. And maybe God will use that technology to reform the church so we are more interested in the gospel and less in property and in stuff because tech will take it away from us and we'll actually have to worry about people."

He further observed that many people, Christians included, are experiencing this unique moment of exponential growth in technology in a way that has never been felt before, a feeling that can be unsettling. Whereas inventions like the printing press and the steam engine punctuated history in ways that fundamentally changed how human beings interacted with each other, technological breakthroughs are occurring so quickly it is hard to keep track. And the potential for seemingly everything to change all of a sudden is now a reality.

For Christians who spurn most technology or find the idea of becoming a modern day Luddite appealing, Benek urges them to consider what happened to the actual Luddites, the bands of English textile workers and weavers who in the early 19th century destroyed machinery, especially in the cotton and woolen mills, the technology they believed threatened their livelihoods.

"The thing to remember about the Luddites is that technology still won. It's still won the day. The tech is coming; the question is whether or not we are going to address it," Benek said.

While in Japan conversing with the roboticists, Benek ended up sharing key parts of the gospel message, telling them that God made them to be co-creators with Jesus Christ and that He cares about what they do, that they are part of the redemption of the world.

"This one woman choked up and raised her hand," he recounted, and she said through tears, "You mean God cares about me?"

"If that doesn't speak to the need as church people, then what the heck are we doing? We need to get out there and connecting with people in ways that are real, and we need tech people to come along and scoop some pastors up and say, 'you know what, we need you in this field.'"