Holocaust survivor shares harrowing story, urges Americans to 'call out' religious persecution

A Holocaust survivor shared her story of pain and loss to encourage the international community to “stand up, call out religious and ethnic intolerance and persecution, and work toward the idea of never again.”

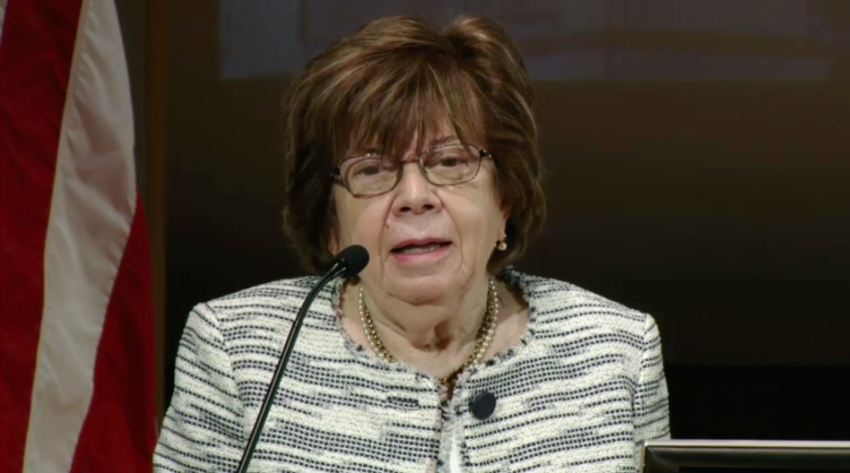

Theodora Klayman shared her story Wednesday during a National Prayer Breakfast sideline event on religious persecution worldwide co-hosted by the Holocaust Museum in Washington, D.C. and 21Wilberforce.

Born in 1938 in Zagreb, Yugoslavia, Klayman was 7 years old at the end of World War II.

“I still do remember, so I will speak about that,” she said.

She described Yugoslavia as a country “cobbled together after World War I” and made up of “differing historical alliances, many religions, several languages,” and “serious ideological and political disagreements.”

These disagreements resulted in the formation of an ultranationalist group known as the Ustaša, who broke off from the Yugoslav establishment and collaborated with the Nazis. With the support of Nazi Germany, the Ustaša ruled the Independent State of Croatia, “eager to persecute anyone who was not politically conservative, Croatian, and Catholic,” Klayman said.

Klayman’s grandfather was a Jewish Rabbi who had served as the community rabbi for more than 40 years and taught religion courses in the local school alongside the Catholic priest. She described her family’s relationship with their predominantly Catholic neighbors as “very cordial.”

“For the forty years my family lived there, practically no anti-Semitic incidents occurred in that area,” she recalled.

But just a few months after the Nazis invaded Yugoslavia, Klayman’s parents and infant brother, Zdravko, were arrested. Her father was deported to the notorious Jasenovac concentration camp and their mother to Stara Gradiska, a subcamp of Jasenovac.

Fortunately, their housekeeper was able to get Zdravko released from jail. Both children were taken to Ludbreg, where they were cared for by their grandparents.

“But by 1942, the entire reaming Jewish community of Ludbreg was deported, including my family members,” she said. “All were soon killed.”

Klayman and her brother were left behind with their mother’s sister and her Catholic husband, Ljudevit. However, in 1943, Ljudevit was arrested on suspicion of supporting the partisan resistance movement and sent to Jasenovac. In his absence, his wife was arrested and deported to Auschwitz, where she soon died from an intestinal illness.

Meanwhile, Klayman and her young brother hid with their neighbors, the Runjaks, and pretended to be their children.

“Most people knew we were the Rabbi’s grandchildren and were aware where we were hiding, but they never denounced us,” she said.

After liberation, Ljudevit, realizing that Klayman and Zdravko’s parents had been killed, legally adopted the children. He was concerned for their well-being, she recalled, especially as the local priest had made “veiled threats” against them.

“He then made the decision to have my brother and me baptized for added protection,” she said.

The family of three attempted to rebuild their lives. Eventually, Klayman moved to Switzerland. She married Daniel Klayman, a Jewish American research chemist, in the fall of 1958, and the two later they settled in the Washington, D.C., area with their two children.

The recipient of degrees from the University of Maryland in French and in teaching English as a second language, Klayman taught in the Maryland public school system for 30 years.

“The history of the Holocaust, my history, highlights the precariousness of persecuted people and the power of individuals, even whole towns, to stand up and do what is right even in extraordinary times," she said.

Klayman emphasized she will forever be grateful to those who fought against the Nazis and those who sheltered and protected her and her brother, risking their own lives to do so.

“Tragically we all know that such hatred, even genocide, did not end with the Holocaust,” she said. “We are here this morning to highlight the experiences of people who are being persecuted today solely for their religious or ethnic identity. Leaders and laypeople have the capacity to act, they must now summon the will to do so.”

Klayman said she hopes her story inspires listeners to “stand up, call out religious and ethnic intolerance and persecution, and work toward the idea of never again.”