Important Religious Aspects of World War I Have Been Ignored, Argues Scholar in New Book, 'The Great and Holy War'

A historian has argued in a new book that the religious aspects of World War I have been largely ignored by scholars.

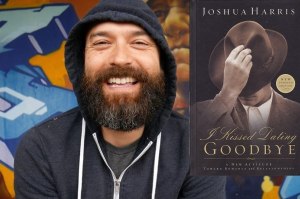

Philip Jenkins, author, distinguished professor and member of the Institute for Studies of Religion at Baylor University in Waco, Texas, believes that people living and fighting in World War I held strong spiritual convictions of various kinds.

Jenkins documents these many examples in his newest book, The Great and Holy War: How World War I Became a Religious Crusade.

In an interview with The Christian Post, Jenkins explained that he felt compelled to write the book due to his sense that "religion had really dropped out of the standard picture of the war."

"It was a very major part of the war as it was understood at the time, but it had dropped out in the later historiography. So I was trying to bring that back," said Jenkins.

Jenkins told CP that when researching his book, he found much in the primary sources of governments, preachers, intellectuals and others in Christian Europe, who felt that the war had a sacred attribute to it.

"Martyrdom, sacrifice, and the idea that people engaged in the war are holy warriors who will go to paradise on the basis of their participation in the war," said Jenkins. "A lot of ideas that we certainly don't think of in the context of Christianity, but which were the standard currency of Europe and America at the time."

The massive reaction

Also known as the "great war" or the "war to end all wars," World War I began in 1914 with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and ended November 1918.

The conflict had many results, including millions of lives lost, the advent of numerous battlefield technologies, and the rise of the Soviet Union.

Jenkins told CP that as time progressed, scholars and writers on World War I focused far less on the religious aspects of the conflict, despite their pervasive presence.

Jenkins attributed this shift, in part, to being made from the 1920s onward, as the modern narrative of the war being a great waste became the norm.

"I think what happened was that during the late-1920s into the '30s, there was a massive reaction, there was a sense of disillusion, mainly among elites," said Jenkins.

"People got absolutely focused on rival secular ideologies … As time went on, people became more reluctant to treat religious motivations in politics seriously at all."

Visions and miracles

Despite the trend to consider nationalism as the chief reason for the war and to dismiss other factors as "window dressing," Jenkins documents in his book many religious arguments for war that influenced people's thinking at the time.

All sides had clergy declare that God was on their side and their opponents were enemies of Christianity. Spiritual thinking and ideas spread rapidly among soldiers and their families at home.

As battlefield fatalities began to enter the hundreds of thousands, many argued in print or in speeches that the End Times were drawing near.

Jenkins told CP that for each nation, religion and nationalism seem to work in concert and it was difficult to determine which entity was leading the charge. This contrasted with the common perception that it was simply elites using religion to advance the cause.

"I was finding a very different picture, whereby the political ideology was being made by the theologians, preachers and the priests and the government was kind of going along," said Jenkins.

"So I still don't think it's absolutely coming from one side or the other, but the two are very much in dialogue."

This spiritual component went beyond what many may realize.

For example, the "Our Lady of Fatima" apparition experienced by Portuguese villagers in 1917 is well known in the modern day, especially in Catholic circles.

Less remembered was that Fatima was one of several miraculous visions claimed by Protestants, Catholics and Orthodox during the war, as many reported seeing angels, the Virgin Mary or ghosts.

British soldiers claimed that during one battle the ghosts of Medieval English long bowmen fired arrows into German ranks; at certain times Russian, German and French soldiers claimed to see the Virgin Mary above their trenches.

A widely circulated story in France had it that at one moment dead Frenchmen rose again briefly to defend a still living comrade from German attack.

This spiritual upheaval also influenced intellectuals of the day. Jenkins wrote that while at a hospital then atheist C.S. Lewis began reading Christian apologetic works.

100 years later

Released last month, The Great and Holy War comes at a time as the 100th anniversary of the beginning of World War I occurs.

Several books have been released to mark the milestone and many ceremonies for remembrance, especially in Europe, are slated to take place.

Jenkins told CP that he hopes this generation will learn more about the conflict, especially the way in which religions, like European and American Christianity, contributed to the bellicose spirit of the time.

"We tend to see the Christian willingness to support violent causes as something that is of the crusading era and it's very regrettable," said Jenkins.

"I would suggest that churches, great churches, have been willing to succumb to these temptations much more recently and that should make us pay serious attention."