‘Keep the gate open’: Latin American leader shares hopes, expectations for Lausanne 4

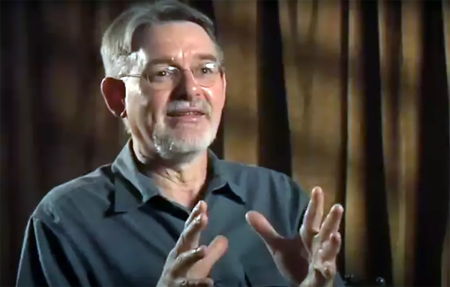

“Will there be room for new voices, will there be space for surprise?” asked Valdir Steuernagel in a speech he gave at a meeting of Latin American leaders in the lead-up to Lausanne’s Fourth Global Congress (Lausanne 4) in Seoul-Incheon, South Korea, that begins Sunday.

Calling for a renewed affirmation of the Evangelical identity and encouraging new conversations involving Evangelical leaders from every part of the world, Steuernagel traced the history of the movement back to its beginnings in 1974.

He recalled significant breakthroughs and ongoing tensions, offered new and timeless perspectives on global missions, recognizing that the task of the Great Commission is still unfinished. He concluded with his prayer for what is expected to be a significant event in Church history.

Back in September 2023, the Lausanne Movement’s regional leaders in Latin America convened a consultation in Montevideo, Uruguay, that featured keynote speakers Valdir Steuernagel, Norberto Saracco (Argentina), Karen Bomilcar (Brazil) and Jaime Memory (United Kingdom). It was part of the lead-up to Lausanne 4 where each region would guide participants through a process that would prepare them for the global event where some 5,000 Christian leaders from every corner of the world will strategize about world missions.

Steuernagel’s speech captured the region’s perspective so well that World Vision Latin America, together with the regional Lausanne leadership, published an edited version in English that would provide a conversation starter not only for Latin Americans but also for participants from around the world.

A prominent theologian and esteemed Brazilian Evangelical leader, Steuernagel served on the Lausanne Central Committee for several years and has intimate knowledge of the movement. He was also president of World Vision’s International Board as well as a member of the World Evangelical Alliance’s International Council, among various other roles he held over the decades of his ministry.

The history and ‘Spirit’ of Lausanne

“For decades, the Lausanne Movement has been a part of my life. I am a kind of ‘child of Lausanne,’ although a belated one,” Steuernagel said, noting that he wasn’t present at the International Congress on World Evangelization held in the city of Lausanne, Switzerland, in 1974, nowadays referred to as Lausanne 1.

The global event convened by Billy Graham and Jack Dyan brought together 2,300 participants from 150 nations, and — under the guidance of theologian John Stott — produced the landmark Lausanne Covenant that remains influential to this day.

“Lausanne 1 was indeed a breath of the Spirit that surprised the broader Christian family and left its mark on the Evangelical world, which was already emerging as a significant stream within the global Christian community,” Steuernagel said.

The event “catapulted the Evangelical world, both internally and externally, into a new self-perception, into a visibility hitherto unknown, and into the need to become a dialogue partner with other Christian groups and with the contemporary world itself.”

It came at a time of increased missionary activity, growth in the Church, expanding resource mobilization and the emergence of international leaders and respected personalities, such as the late Graham.

“Evangelicals now filled stadiums, captivated large audiences, and used television as they had previously done with radio,” Steuernagel said, noting that the Gallup report marked 1966 as the ‘Year of the Evangelicals’ in North America.

But as 1974 came around, it became evident that it was indeed a global phenomenon “as there was an Evangelical church flourishing in many other places, notably in various African countries, many Latin American countries, and some Asian countries.”

Lausanne 1 recognized this change at the event and adapted to the contemporary world, as was expressed in the Lausanne Covenant.

Steuernagel emphasized that it was done “in an Evangelical style. A style that never considered giving up its identity, affirming, therefore, the centrality of Jesus, the authority of Scriptures, human sinfulness, the missionary calling of the Church, and the hope for a new Heaven and a new Earth.”

But what also happened at the event is that “the gate was open for new conversations” and “open to accentuate identity and mission,” he said, as North American missionary and evangelistic organizations increasingly became international, while national churches brought new perspectives to the conversations.

“It is worth noting that Lausanne 1 was a pioneer in allowing the growing Evangelical diversity, with a strong ethnic-geographic aroma, to take the stage, without forgetting how much this diversity was already present in the audience.”

According to Steuernagel, the development brought “an element of shock and surprise” to Evangelical culture that historically struggled with diversity. And he added that “[this] shock and surprise manifested as a latent and continuous tension in the Movement.”

It is important for participants of the upcoming Congress to understand these historical dynamics as they continue to this day and will likely be felt at Lausanne 4 once again, he asserts.

‘Evangelization’ versus ‘total mission of the church’: Emerging voices from the Global South

It became clear early on that Lausanne 1 would be followed by a Continuation Committee, which then met for the first time in January 1975 in Mexico City. It was there that “tension emerged with significant visibility,” Steuernagel said.

In seeking to define Lausanne’s mandate, the question arose whether it should be specifically focused on evangelizing the unreached, i.e. proclamation, or whether it should emphasize the “total mission of the church,” i.e. a more holistic approach, which the Lausanne Covenant already affirmed.

The committee struck a balance, saying they understood that “‘the advance of the church’s mission’ means encouraging all the people of God to go into the world as Christ was sent into the world, giving themselves to others in a spirit of sacrificial service, with evangelism being primary in this mission.”

Tensions persisted, however, as leaders from what then became known as the “Global South” continued to speak up.

“These voices reflected the journey of young churches and emerging Christian leaders in search of a relevant Christian experience for their context and in pursuit of a dialogue with their respective realities, questions, cries, and experiences,” he said. “Voices that raised critical questions about an evangelistic practice that emphasized soul salvation at the expense of living an incarnate faith.”

These concerns had been raised at Lausanne 1 by Latin American leaders René Padilla and Samuel Escobar, with Padilla addressing the theme of “Evangelization and the World,” and Escobar discussing “Evangelization and the Quest for Freedom, Justice and Fulfillment by Man.”

They advocated for an evangelistic practice with cultural sensitivity, a missional experience expressed in social responsibility and the pursuit of justice, and a life marked by simplicity and sacrifice, as found and modeled by Jesus, Steuernagel said.

Global South leaders celebrated the Lausanne Covenant’s emphasis on mission “that encompasses all areas of life throughout one’s life.” Leaders mainly from North America, however, raised concerns “about the need to maintain a focus on the verbal proclamation of the Gospel and on spiritual and personal conversion.”

Steuernagel recounted that in 1975, John Stott responded to some of these concerns by noting the lack of Global South representation at the Mexico meeting and the “insensitivity with which some North Americans” emphasized the need to “restrict to evangelism” and not focus on broader concerns as expressed in the Covenant. And in an article titled “The Meaning of Lausanne,” Stott later wrote that he believed regional groups would find their way according to their own discernment.

Christian Daily International provides biblical, factual and personal news, stories and perspectives from every region, focusing on religious freedom, holistic mission and other issues relevant for the global Church today.