Legislative support grows for physician-assisted suicide in NY but some churches, doctors oppose it

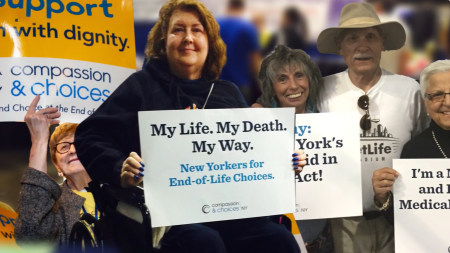

Advocates of physician-assisted suicide lobbied lawmakers in New York Tuesday to pass legislation that would make it legal for terminally ill patients to request and use medication to end their lives, but many local leaders in the Catholic Church and health experts oppose it.

Activists like Corinne Carey, senior campaign director for Compassion & Choices NY & NJ, who says she has been pushing to make physician-assisted suicide legal in New York for nearly 10 years, argues that it would be an act of love if lawmakers were to vote to have New York join 10 other states in the U.S., and the District of Columbia, where physician-assisted suicide is legal.

“We have been here for almost a decade, every single year asking the Legislature to pass New York’s Medical Aid in Dying Act,” Carey told supporters during a rally in Albany on Tuesday.

“How often do lawmakers have a chance to do something that’s all about love, all about compassion, that 72% of New Yorkers want to see, that 50 prominent statewide organizations are calling for them to do,” she said.

Carey expressed optimism, that the legislation to allow physician-assisted suicide in New York could happen this year because of growing support from a broad coalition of advocates, including groups from “all religious experiences.” About 80 legislators are sponsoring the bill.

“People from both sides of the aisle, from all religious experiences, and all backgrounds are asking them to do [this],” Carey said. “This is an opportunity for lawmakers to do something relentlessly positive for New York families and we are confident they can do it this year.”

A995A and S2445A are the two bills being considered by the New York Assembly and New York Senate, respectively, to allow physician-assisted suicide in the state, but Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New York, Cardinal Timothy Dolan, believes the bills should be rejected because the reasons why patients choose physician-assisted suicide are not necessarily because of their medical status.

“Experts tell us that physical pain is not the primary reason why people request PAS. The main reasons are fear of being a burden on others, anxiety over loss of autonomy, and worry about the disappearance of enjoyable activities,” Dolan wrote in an op-ed for the New York Daily News. “What a terrible thing to legalize and recommend suicide in these situations!”

In a recent pastoral statement on the proposed legislation, the Rev. John O. Barres, bishop of Rockville Centre, raised concern that in countries like Canada where physician assisted suicide has been legal since 2016, lawmakers have already expanded the group of people who are legally allowed to end their lives.

“What is being peddled by advocates as a last resort for those suffering from interminable pain will very quickly be expanded to resemble the dystopian nightmare we are seeing play out in Canada, which passed a law very similar to the New York bill in 2016 but which already has been expanded to allow people with non-terminal diagnoses to end their lives,” Barres said.

“In March, an Ottawa judge approved assisted suicide for a young woman whose only diagnoses are autism and ADHD, over her parents pleading objection. The Canadian law is set to expand again in 2027 — incredibly — to allow people with mental illnesses like depression, anorexia, or bipolar disorder to access suicide pills.”

Just last month, after years of opposing the legislation, the Medical Society of the State of New York announced that it now supports the Medical Aid in Dying Act.

“MSSNY supports legislation such as the medical aid in dying act and supports physicians’ choice to opt-in or decline to engage in the processes and procedures as outlined in any proposed medical aid in dying legislation,” the organization said in a release.

In an op-ed for the Psychiatric Times, titled, Did California Dodge a “Right-to-Die” Bullet?, psychiatrists Mark S. Komrad, Annette L. Hanson, Cynthia M.A. Geppert and Ronald W. Pies argued that physician-assisted suicide is not medical care and affirmed the American Medical Association’s position that it is “fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as healer, would be difficult or impossible to control, and would pose serious societal risks.”

“The more PAS and euthanasia are viewed as medical care, the easier it becomes to enlarge the eligibility criteria to encompass almost anyone who feels they are ‘suffering,’” the doctors argued.

“Then the slide down the slope can accelerate, from terminal conditions to chronic conditions (such as mental illness), as is happening in our culturally and geographically adjacent neighbor, Canada,” they explained. “That opens the path for the next drift in the evolving ethos — transforming one’s ‘opportunity’ to seek these lethal procedures into the virtue of relieving loved ones from the burden of their condition.”

On Wednesday, a group of doctors, nurses, nursing assistants, medical residents and medical students who work for either the Columbia Vagelos College of Physicians & Surgeons or New York Presbyterian Hospital also opposed the proposed legislation in a statement.

The group, which is officially known as the Columbia Biomedical Roundtable, has members “with religious faith and those without.”

“Consider that while most of us think in terms of an ongoing relationship with our primary doctor, most New Yorkers are not privileged to have their own primary doctor. Thus, a prescriber who hardly knows the patient may be asked to take responsibility for his/her death. This is why in the name of personal ‘autonomy,’ those who will suffer the most from ‘letting the genie out of the bottle’ are the most vulnerable among us,” the healthcare workers noted. “Those at highest risk are those with disabilities or mental health or behavioral conditions, black and brown people, and those unable to access necessary medical care.”

They noted that since physician-assisted suicide was legalized in Canada in 2016, some 60,000 people have voluntarily chosen to die by prescription, including 16,000 last year alone.

“In Canada, this law is on pace to account for five percent of all deaths by 2025. In some urban areas of the Netherlands where this law began in 2002, 12-14% of deaths occur by that means,” the statement explained.

The healthcare group further noted that even though physician assisted suicide hasn't yet been approved for mental illness, a 27-year-old woman with autism in Canada was allowed to end her life over her father’s objections.

“By whatever name you call it, this notion changes medicine forever by engaging doctors to extinguish human life, turning them from healers to active participants in killing a patient. This is diametrically opposed to the aspirations of the healing profession. It turns medicine on its head. Giving a patient a prescription for a lethal dose of drugs is the medical equivalent of handing the patient a loaded pistol,” the group said.

“While every terminally ill, suffering patient ought to invoke compassion, suicide is not the answer. Rather, we must strive to improve end-of-life care. Legislators and heath care professionals in New York state must work together to obtain the resources to relieve each individual person’s various forms of pain. But sanctioning suicide is not the answer.”

Contact: leonardo.blair@christianpost.com Follow Leonardo Blair on Twitter: @leoblair Follow Leonardo Blair on Facebook: LeoBlairChristianPost