Overcoming Misconceptions About Homelessness

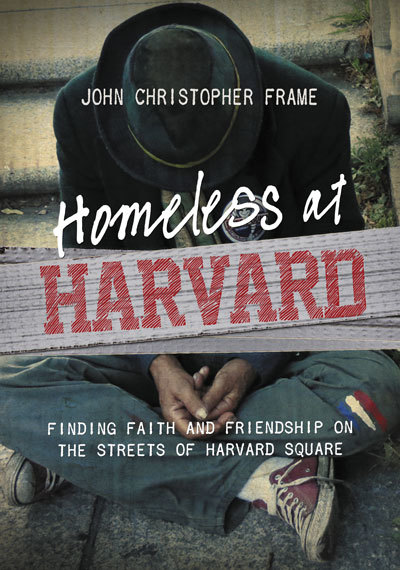

I'm not an expert on homelessness. I can't recite facts and figures about the issue without looking them up first. I haven't delved into the heaps of research about the subject by social scientists. My guess is that, among the true experts on homelessness, are the people who have actually lived on the streets day in and day out. Neal and George, for example, are two of the four men featured in my book, Homeless at Harvard, who've worn tread on Harvard Square's sidewalks for years, and have openly shared their stories.

When I spent a summer with the homeless community in Harvard Square, Neal and George were among the homeless people I spent time with. And in Homeless at Harvard, Neal and George share some of the hardships of life on the streets, in their own words. They talk about addiction. They open up about their hopes for the future. They tell us stories of their experiences around Harvard Square, like an older generation reminiscing of times long past. And while Neal shares his disappointments about not finding housing, he acknowledges that he could get bored if he stayed indoors too much. And while George has found some of his street experiences appealing in some ways, he balances those feelings with his desire for stable living conditions.

It's easy to develop misconceptions about people, including the homeless. And it's usually because we don't know the people we have misconceptions about. We're more likely to think telemarketers are annoying, not parents working to put food on their tables. We're more likely to think elected officials are self-serving, not community members committed to public service. We're more likely to think men sleeping on park benches are loners, not brothers, sons and dads craving a different life.

It's easy to generalize people with simple and conclusive terms. But seeking to understand people helps us better realize and discover the circumstances and complexities of their lives. It helps disrupt our misconceptions about them.

It's possible, of course, that what we may have thought to be a misconception about a person actually turns out not to be a misconception, after all. Sometimes, in understanding someone, we find out our preliminary thoughts about him or her were right. But sometimes we're wrong. And even if we were right, communicating with someone will help us better understand the complexities of his or her life. By understanding people as individuals, we realize that they shouldn't be generalized or mass-classified into one overarching misconception.

One misconception some of us have about homeless people is that they all have chosen their lifestyle. "They choose to be homeless," we say. Maybe they even like to be homeless, we think. Such thoughts relieve us from any responsibility we might feel toward those living on the streets.

People who are living on the streets, though, have often undergone various circumstances that have landed them there. Everyone's situation is unique. Maybe they've struggled with substance abuse or have a mental illness. Maybe they've experienced domestic violence, loss of employment, or family turmoil. Maybe it's all of the above. Maybe it's none of the above.

Sometimes, life's circumstances are out of our own control. Sometimes the choices we make have been influenced by parents or friends. Sometimes our "choices" haven't been choices at all, but were made for us by parents or friends, or the lack of parents and friends. For some, life has taken them down rocky and winding paths – ones they feel they've traversed long past any point of returning. They've lost hope, or maybe they never had it.

Homelessness is a complex issue. Life in general is complex. When we understand that, we better understand human struggle. Struggles we all face are better understood when we understand them within their complexity.

So how do we begin to understand the complexities of life?

We begin by engaging more deeply with people near and far. We talk to people we don't know and, in return, meet new acquaintances we wouldn't have otherwise met. We more regularly become involved in our communities – perhaps by assisting at a charity (such as a drop-in center for the homeless), volunteering at the local library, or even picking up litter in a city park. Hopefully, engaging more with people will positively affect them, our communities and world, and us, too. When we engage more deeply with people, we're likely to gain new understandings of them. We might feel a new level of insider-ness, or familiarity and responsibility where previously there was distance. By assisting at a drop-in center, for example, we might develop a more natural connection to homeless people we'd see at other times. By volunteering at the library, we might connect with others who are also interested in making a difference in the community, or we might strike up conversations with homeless people who use the library as a day shelter. By picking up litter in the park, we might feel more inclined to speak with someone there, whether that person is homeless or just lonely and needs to talk.

Acts of service introduce us to life beyond our current social circles. When engaging with those around us, we feel a greater sense of responsibility toward them. We're pushed to look at life from different perspectives. We think about working to solve our community's social problems, or at least become more aware of them.

When acts of service become part of our daily schedules, service to others becomes part of our lives. As a result, people's stories become intertwined with our own stories and new stories develop – ones that can transform us, the people we connect with, and our communities. And that's helpful for everyone – the housed and the homeless, the mainstream and the marginalized.

When we purposefully engage with an easy-to-misunderstand world, we better realize and respond to its complexities, and better relate to our communities, whomever they include. Being more deeply connected with our communities brings value to others and us. And it leads to our overcoming misconceptions about the people we have yet to meet.