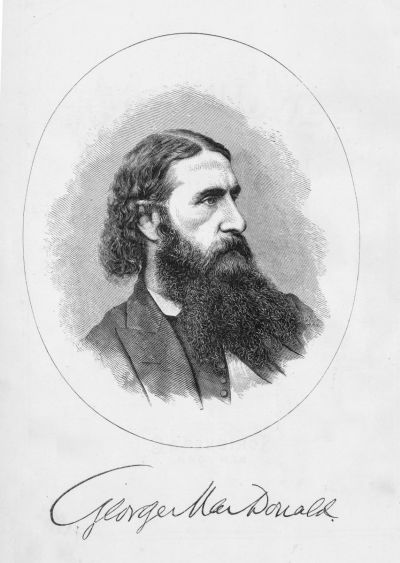

George MacDonald and the Christian imagination

December 10 was the birthday of a man regarded as the father of modern fantasy literature, someone who profoundly influenced writers such as G.K. Chesterton and C.S. Lewis. Though the writing of pastor and author George MacDonald often lacked theological precision, his legacy includes inspiring some of the most important Christian fiction of all time. Like Tertullian and Origen, fathers of the faith whose theology veered away, at times, from orthodoxy, the bulk of MacDonald’s work has served to enliven the Christian faith of future generations.

MacDonald came from a highly literate family, including scholars of Celtic mythology and collectors of fairy tales. Raised in a strongly Calvinistic congregation, members of his family came from a range of denominations. In 1850, after university and ministry training, MacDonald became the pastor of Trinity Congregational Church in Arundel. Because of his occasional unorthodoxy, his sermons often earned the ire of the congregation. As a result, his salary was reduced by half, and he resigned from the church in 1853.

Eventually, MacDonald began teaching at the University of London. His first book, Phantastes: A Faerie Romance for Men and Women, was published in 1858. His series of fantasy stories, fairy tales, novels, nonfiction and poetry that followed made him an important literary figure and influenced dozens of writers on both sides of the Atlantic, including Lewis Carroll, whom he mentored and encouraged to publish Alice in Wonderland. He also influenced the likes of Mark Twain, Oswald Chambers, G.K. Chesterton, C.S. Lewis, and J.R.R. Tolkien. In fact, Wikipedia lists 39 major authors for whom MacDonald was a major literary influence.

His very first book, Phantastes, was critically important for C.S. Lewis. In his autobiography, Surprised by Joy, Lewis said that as he read the book,

I saw the bright shadow coming out of the book into the real world and resting there, transforming all common things and yet itself unchanged. Or, more accurately, I saw the common things drawn into the bright shadow. … [I]n the depth of my disgraces, in the then invincible ignorance of my intellect, all this was given me without asking, even without consent. That night my imagination was, in a certain sense, baptized; the rest of me, not unnaturally, took longer. I had not the faintest notion what I had let myself in for by buying Phantastes.

This started Lewis on the road to conversion. He would later refer to MacDonald as his “master” (that is, his teacher). In a similar way, G.K. Chesterton commented that MacDonald’s story, The Princess and the Goblin,

...made a difference to my whole existence, which helped me to see things in a certain way from the start; a vision of things which even so real a revolution as a change in religious allegiance has substantially only crowned and confirmed. Of all the stories I have read, including even all the novels of the same novelist, it remains the most real, the most realistic, in the exact sense of the phrase the most like life.

The Princess and the Goblin is the story of a princess living in a castle besieged by goblins. Why would Chesterton call it realistic and “the most like life”? The answer lies in the peculiar genius at the heart of all of MacDonald’s novels, whether fantasy or not. MacDonald, as Chesterton explained, believed that people really are “princesses and goblins and good fairies” that, in his non-fantasy novels, he portrayed as ordinary men and women. In other words, the truth of this world can often be found in fairy stories. This world, MacDonald believed, is only a disguise for the real story hidden beneath it. Thus, the fairy story is fundamentally more real and contains more truth than “realistic” stories that only offer surface meanings while missing deeper truths.

This insight is echoed in J.R.R. Tolkien’s seminal essay, On Fairy-Stories. In it, he argues that, by including mundane things like bread and wine, fairy stories endow the things we encounter in daily life with new significance and remind us of their true, deeper significance that familiarity can obscure.

Oswald Chambers, author of the famous devotional, My Utmost for His Highest, commented that “it is a striking indication of the trend and shallowness of the modern reading public that George MacDonald’s books have been so neglected.” We need not make the same mistake. MacDonald’s theology was off on some points, such as his particular version of universalism, but the tribute to his books by Christian leaders is a testimony to their value in helping us see the deeper realities behind the commonplace events of our lives.

Why not take some time to read some of his books? Like Lewis, you may find your imagination baptized.

Originally published at Breakpoint.

John Stonestreet serves as president of the Colson Center for Christian Worldview. He’s a sought-after author and speaker on areas of faith and culture, theology, worldview, education and apologetics.

Glenn Sunshine is a professor of history at Central Connecticut State University, a Senior Fellow of the Colson Center for Christian Worldview, and the founder and president of Every Square Inch Ministries. He is a speaker, the author of several books, and co-author with Jerry Trousdale of The Kingdom Unleashed.