'The Book of Redemption': Forgotten ledger restored 100 years after Tulsa Race Massacre

One hundred years ago, violent white mobs launched a horrific siege on the Greenwood District of Tulsa, Okla., a predominantly Black business and residential district that came to be known as “Black Wall Street” for its cultural and economic prowess in the 1910s.

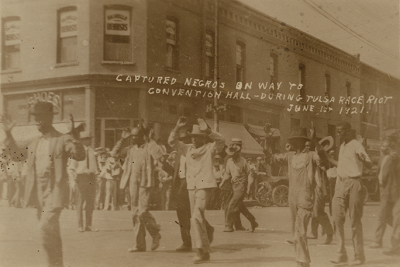

Following unfounded accusations that a Black man, Dick Rowland, had assaulted a white woman, Sarah Page, white Tulsans retaliated by taking up arms and attacking the Greenwood District. From May 31 to Jun. 1, 1921, they destroyed 35 city blocks, burned homes, looted, demolished businesses, schools, churches and a hospital and murdered and maimed hundreds of Black residents. Some scholars estimate 300 people were killed and 800 people were wounded. Tulsa resident Buck Colbert Franklin wrote of aerial attacks in his eyewitness account.

Today, the city continues to investigate mass graves of the victims of the Tulsa Race Massacre. No Black-owned buildings from that time remain, except one: Vernon Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

The church was founded in 1905, two years before Oklahoma achieved statehood. Although the church was badly damaged by fire amidst the terror attacks, it became a refuge for the men, women and children who had lost everything. As community members came together to rebuild their lives, people began donating money to restore the church. By 1928, the main church building had been rebuilt and additional renovations took place in the 1930s and 1940s.

Those who contributed to the renovations had their names recorded in a giving ledger, which lay forgotten in the church’s basement for decades until church members recently discovered it.

Rev. Dr. Robert Turner, the church’s pastor, along with Sarah Stitt, First Lady of Oklahoma, have been working with Museum of the Bible to honor those who helped reconstruct the church and restore the extremely fragile ledger. Later this month the restored ledger, which church members named “The Book of Redemption,” will be returned to its home and will bear witness to our nation about the awful reality of the Tulsa Race Massacre — and how hope was born out of suffering.

At Museum of the Bible, we feel humbled to have been invited to participate in such a momentous project. As Americans commemorate the massacre’s centennial, we will release a video series that will give the members of the Vernon Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church community a platform to tell their story and will document the process of restoring the ledger. We have also created a facsimile of the ledger for people to touch and read through at the church’s commemoration ceremony on May 31.

Sadly, the Tulsa Race Massacre is an often overlooked event in American history. As our nation continues to grapple with relationships among our citizens, I believe we have much to learn from those whose names are recorded in the ledger.

Amidst the anguish of losing loved ones and livelihoods, of being regularly subjected to abuse and assault because of their skin color, the members of Vernon Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church chose redemption.

“To redeem” is to buy or win back, to free from, to make better, to repair, to atone for — these are just a few definitions. “Redemption” is a full word.

In Ephesians 1:7, Apostle Paul writes, “In him [Jesus] we have redemption through his blood, the forgiveness of our trespasses, according to the riches of his grace.” If we desire to reconcile past traumas and to move forward into a more equitable, peaceful future, if we long for redemption in our own national story, then we ought to look to the story reflected in the pages — a powerful refutation of bigotry’s carnage — of “The Book of Redemption.”

Harry Hargrave is CEO of Museum of the Bible.