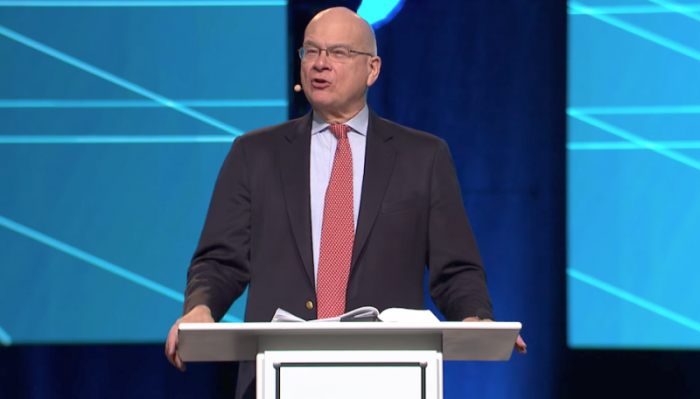

Tim Keller, Christians & Politics

Tim Keller, founder of Redeemer Presbyterian Churches in New York, is one of America's most influential pastors and Christian thinkers. He's a model for successful urban church planters across the nation and overseas. His New York Times editorial Sunday, "How Do Christians Fit Into the Two-Party System? They Don't," (excerpted from his new book) is very thoughtful. But some additional points merit discussion.

Keller offers several themes:

- "Those who avoid all political discussions and engagement are essentially casting a vote for the social status quo."

- "While believers can register under a party affiliation and be active in politics, they should not identify the Christian church or faith with a political party as the onlyChristian one."

- "Most political positions are not matters of biblical command but of practical wisdom."

- "The biblical commands to lift up the poor and to defend the rights of the oppressed are moral imperatives for believers." But, the "Bible does not give exact answers to these questions for every time, place and culture."

- "Jesus forbids us to withhold help from our neighbors, and this will inevitably require that we participate in political processes."

- Finally, Keller warns that "increasingly, political parties insist that you cannot work on one issue with them if you don't embrace all of their approved positions," which Christians must reject.

Keller notes Christians must work for racial justice, which is perceived as liberal, while affirming marriage as union of male and female, a conservative stance in our culture.

These themes from Keller are sound. Space permitting, no doubt he would have elaborated how Christian political witness is pursued and by whom. (Perhaps he does in his book, which I've not yet read.) It seems important, for example, to distinguish among the institutional church, i.e. a denomination or congregation and its employees, versus the universal Body of Christ, versus individual Christians.

Keller's own denomination, the Presbyterian Church in America, adopts virtually no direct political political stances. To my knowledge, Keller's congregations are not overtly politically active in electoral politics or legislation. Keller himself largely has abstained from public endorsements and direct lobbying.

Presumably Keller agrees that the institutional church, including its clergy, don't have a vocation for routine direct engagement in political specifics such as candidate endorsements or intense legislative lobbying. Also presumably he believes the institutional church should offer broad principles about God's purposes for government and Christian duties towards the common good.

And presumably Keller believes the global Body of Christ collectively is a politically redemptive force globally and locally, even as its distinct communions and individual believers have particular unique callings.

Some parts of the Body offer peculiar specialties in social witness not necessarily true for others. Catholicism and Pentecostalism may offer societal emphases different from each other and other communions but still integral to the universal church.

Keller's column implies but likely does not intend to insist that all individual Christians are called to political engagement. All are called to be good citizens, but arguably some best serve society by abstaining. Cloistered religious orders, the Amish, various other separatist communities, and many persons are generous in prayer and charity without direct political witness. They serve God where they are without insisting all others follow their example.

Intense or professional political activism is a special calling likely for very few Christians, as no doubt Keller would agree. Most Christians are called to focus primarily on their families, professions and churches, not politics. If all or most Christians were called to be full-time political activists, the results on the church and the world likely would be very unchristian.

Keller warns against aligning Christianity with a political party. But presumably he would agree that some Christians may individually have callings to intense partisan service. Christians in different and even opposing political movements may have opportunity to leaven broadly and to enact wide providential purpose beyond transient human understanding.

Not all two billion plus professing Christians in the world are called to march in unison to a synchronized political theme. Millions in repressive societies lack significant opportunity for any direct political engagement. But the Body of Christ as a whole prays and works for more just societies more closely aligned with God's desires.

Keller rightly warns of worldly resistance when Christians contend for more just societies. Christian social witness even at its best will always earn mixed reviews. "If we are only offensive or only attractive to the world and not both," Keller concludes, "we can be sure we are failing to live as we ought."

Of course, as Keller also concludes, Christ prevailed by disavowing earthly political power as He announced his eternal kingship. Christian political engagement, even at its very best, is only a foreshadowing of a much greater and more permanent polity. Yet, Christians with callings to political engagement should labor on, with hope.